Showing posts from category: Allgemein

AFD – NSDAP

AFD – NSDAP

Die Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) und die Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) unterscheiden sich in zentralen Punkten deutlich – auch wenn es inhaltliche und rhetorische Überschneidungen gibt, die den Vergleich immer wieder auslösen.

1. Historischer Kontext

-

NSDAP: Entstand nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in einer Zeit von Kriegstrauma, Hyperinflation und dem Zusammenbruch der Weimarer Republik. Sie übernahm 1933 die Macht und errichtete eine totalitäre Diktatur.

-

AfD: Gegründet 2013 in einer stabilen demokratischen Ordnung. Sie agiert innerhalb des Grundgesetzes und nimmt regulär an Wahlen teil.

2. Verhältnis zur Demokratie

-

NSDAP: Lehnte Demokratie offen ab. Ziel war die Abschaffung des Parlaments und die Errichtung einer Führerdiktatur.

-

AfD: Bekennt sich formal zur Demokratie, stellt jedoch wiederholt deren Institutionen (Medien, Justiz, Parlament) infrage und relativiert demokratische Grundprinzipien, etwa die Gewaltenteilung.

3. Ideologie und Menschenbild

-

NSDAP:

-

Biologischer Rassismus (»Arier«, Antisemitismus)

-

Völkische Ideologie

-

Legitimation von Gewalt, Terror und Vernichtung

-

-

AfD:

-

Nationalistisch, teils ethnisch-kulturelles Volksverständnis

-

Abwertung von Migranten und Minderheiten in Teilen der Partei

-

Kein offizieller biologischer Rassismus, aber vielfach anschlussfähig an ethnonationalistische Denkweisen

-

4. Gewalt und Machtmittel

-

NSDAP:

-

Systematische Gewalt (SA, SS)

-

Politische Gegner wurden verfolgt, inhaftiert oder ermordet

-

-

AfD:

-

Keine Parteimilizen

-

Gewalt wird offiziell abgelehnt, jedoch gibt es problematische Nähe zu rechtsextremen Milieus und sprachliche Radikalisierung

-

5. Antisemitismus

-

NSDAP: Zentraler Kern der Ideologie, führte direkt zum Holocaust.

-

AfD: Offiziell distanziert, aber wiederholt Relativierungen der NS-Verbrechen.

6. Wirtschaftspolitik

-

NSDAP: Staatsinterventionismus kombiniert mit Kriegswirtschaft.

-

AfD: Marktradikal bis neoliberal, wirtschaftspolitisch eher bürgerlich-konservativ.

7. Fazit

AfD ≠ NSDAP.

Die AfD ist keine nationalsozialistische Partei und keine Diktaturbewegung.

Aber:

-

Sie nutzt ähnliche Feindbilder,

-

ähnliche Delegitimierung demokratischer Institutionen,

-

und eine Radikalisierungsrhetorik, die historisch belastet ist.

Der Vergleich ist daher politisch warnend, nicht historisch gleichsetzend.

Antidemokraten

Warum lehnten Schmitt, Spengler und Moeller die Demokratie ab?

Audio

Die Weimarer Republik war nicht nur politisch instabil – sie war auch geistig umkämpft. Einige der einflussreichsten Intellektuellen ihrer Zeit entwickelten fundamentale Kritik an Liberalismus und parlamentarischer Demokratie. Besonders prägend waren Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spengler und Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.

Ihre Argumente sind historisch – aber sie wirken bis heute nach.

Carl Schmitt: Entscheidung statt Debatte

Carl Schmitt war Staatsrechtler und wohl der schärfste Kritiker des Parlamentarismus. Für ihn lebte das Parlament ursprünglich von ehrlicher, öffentlicher Diskussion. In der Realität sah er jedoch Parteitaktik, Machtinteressen und Kompromisspolitik.

Sein berühmter Satz lautet:

„Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet.“ ???

Schmitt meinte: In echten Krisen brauche ein Staat klare Entscheidungen – keine endlosen Debatten. Demokratie verstand er nicht als Wettbewerb verschiedener Meinungen, sondern als politische Einheit eines homogenen Volkes. Pluralismus erschien ihm als Schwäche.

Ich: Das Leben ist nicht einfältig, sondern vielfältig. Der Staat muss dieser Vielfalt gerecht werden, indem er vielfältiges Leben ermöglicht, weil sonst sehr viele leiden.

Als ob Hitler und die Nazis keine Machtinteressen gehabt hätten, als ob die Entscheidungen Hitlers immer gut gewesen wären. Er hat schließlich Deutschland und die Welt in die schlimmste Katastrophe geführt. Dasselbe kann man von Cäsar, Stalin, Mao…praktisch von jedem Diktator sagen.

Vielfalt Oswald Spengler: Demokratie als Zeichen des Niedergangs

Spengler war Kulturphilosoph. In seinem Werk „Der Untergang des Abendlandes“ beschrieb er Kulturen wie Organismen mit Aufstieg und Verfall. Die westliche Welt sah er bereits im Stadium des Niedergangs.

Demokratie bedeutete für ihn nicht Herrschaft des Volkes, sondern „Herrschaft des Geldes“. Medien und Parteien würden von wirtschaftlichen Interessen gesteuert. Am Ende stehe nicht mehr Demokratie, sondern der „Cäsar“ – eine starke Führerfigur.

Für Spengler war autoritäre Herrschaft weniger Ideologie als historische Konsequenz.

Ich: Jeder Diktator und jede Diktatur war bisher ein Fluch für die Menschheit. Das hängt wesentlich mit der Beschaffenheit des menschlichen Gehirns zusammen. Jede Diktatur teilt das Volk in Anhänger und Gegner ein. Die Anhänger bekommen alle Privilegien und können Reichtum scheffeln, die Gegner werden benachteilgt, verfolgt, oft ausgerottet.

Nur in einer Demokratie werden die Menschen zur Mündigkeit angeleitet und nicht zum Buckeln und Lügen. Außerdem muss es zur Kontrolle der Regierung Meinungs- und Pressfreiheit geben, was es in autoritären Staat nie gibt.

Demokratie ist also nicht Niedergang, sondern erwachen zur Mündigkeit und Mitsprache.

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck: Einheit statt Parteien

Moeller van den Bruck lehnte sowohl Liberalismus als auch Marxismus ab. In seinem Buch „Das Dritte Reich“ forderte er eine nationale Erneuerung Deutschlands.

Parteien und Parlament galten ihm als Ausdruck von Zersplitterung. Stattdessen propagierte er eine autoritär geführte Volksgemeinschaft. Sein Begriff „Drittes Reich“ war ursprünglich als geistiges Erneuerungsprojekt gedacht – wurde später jedoch politisch anders besetzt.

Er gehört zur sogenannten „Konservativen Revolution“, einer Strömung, die die demokratische Moderne überwinden wollte.

Ich: Ich frage mich auch immer, warum es überhaupt Leute geben darf, die anderer Meinung sind als ich, wo doch ganz klar ist, dass ich die einzig richtige Meinung habe. Warum können nicht einfach alle Leute so sein wie ich bin und so denken wie ich denke, dann gäbe es nämlich die Einheit.

Was verbindet diese Denker?

Trotz unterschiedlicher Ansätze zeigen sich klare Gemeinsamkeiten:

-

Ablehnung des Liberalismus

-

Skepsis gegenüber Parteien und Parlament

-

Kritik am Pluralismus

-

Betonung politischer Einheit

-

Offenheit für autoritäre Führung

Demokratie galt ihnen als schwach, unehrlich oder dekadent.

Warum ist das heute noch relevant?

Diese Ideen sind nicht verschwunden.

Schmitt wird bis heute in Debatten über Ausnahmezustände und staatliche Souveränität diskutiert. Spenglers Niedergangsdiagnosen tauchen immer wieder in Krisenzeiten auf. Moeller dient manchen Strömungen als ideengeschichtlicher Bezugspunkt.

Die zentrale Frage bleibt aktuell:

Wie viel Streit hält eine Demokratie aus – und wie viel Einheit braucht sie?

Moderne Demokratietheorie beantwortet das anders als diese Autoren: Konflikt und Pluralismus gelten nicht als Schwäche, sondern als Wesensmerkmal demokratischer Freiheit.

Demokratie bedeutet Rechtsstaatlichkeit, Machtbegrenzung, Machtkontrolle, sowie Mitsprache und Teilhabe der Bürger.

Autokratie hingegen heißt Willkürherrschaft, Machtmissbrauch, Vetternwirtschaft und das Festklammern von Eliten und Familienclans an der Macht…bis zur Schmerzgrenze des Volkes. Siehe: Iran

Messias

Weltentstehungsmythen

Weltenstehungsmythen

Von Chaos zur Ordnung – Die wichtigsten Schöpfungserzählungen der Menschheit

1. Mesopotamien (ca. 2000–1200 v. Chr.)

Enuma Elisch: Der Gott Marduk besiegt die Urgöttin Tiamat. Aus ihrem Körper entstehen Himmel und Erde. Der Mensch wird geschaffen, um den Göttern zu dienen.

2. Ägypten (ca. 2000 v. Chr. und älter)

Am Anfang existiert das Urwasser (Nun). Daraus erhebt sich der Sonnengott, der weitere Götter erschafft und die Welt ordnet.

3. Indien – Rigveda (ca. 1500–1200 v. Chr.)

Purusha-Hymne: Der kosmische Urmensch wird geopfert. Aus seinen Körperteilen entstehen Welt und Gesellschaft.

4. Hebräische Tradition (ca. 1000–500 v. Chr.)

Genesis: Gott erschafft die Welt in sechs Tagen durch sein Wort. Der Mensch wird als Ebenbild Gottes geschaffen.

5. Griechenland (ca. 700 v. Chr.)

Aus dem Chaos entstehen Gaia und Uranos. Nach mehreren Göttergenerationen übernimmt Zeus die Herrschaft.

6. China (überliefert ab ca. 300 v. Chr.)

Pangu: Aus einem kosmischen Ei entsteht Pangu. Er trennt Himmel und Erde. Sein Körper wird zur Welt.

7. Nordisch-germanische Tradition

Im leeren Raum Ginnungagap entsteht der Urriese Ymir. Die Götter formen aus seinem Körper die Welt.

8. Rom (1. Jh. v. Chr.)

Aus dem Chaos bringt eine göttliche Macht Ordnung in Himmel, Erde und Meer.

9. Maya – Popol Vuh

Die Götter erschaffen mehrfach Menschen. Erst der Mensch aus Mais gelingt dauerhaft.

10. Islam (7. Jh. n. Chr.)

Allah erschafft Himmel und Erde in sechs Zeitabschnitten. Adam wird aus Lehm geformt.

Gemeinsame Motive

- Chaos oder Urwasser am Anfang

- Ordnung durch göttliche Macht

- Schöpfung durch Wort, Kampf oder Opfer

- Besondere Rolle des Menschen

Zentrale Vergleichsmotive

| Kultur | Anfangszustand | Wie entsteht die Welt? | Rolle des Menschen | Besonderes Motiv |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judentum / Christentum | Formlose Erde, Finsternis | Gott erschafft durch sein Wort (Bibel) | Ebenbild Gottes | Schöpfung durch Sprache |

| Islam | Himmel und Erde ungeordnet | Allah erschafft in sechs Zeitabschnitten (Koran) | Statthalter Gottes | Göttliche Allmacht |

| Griechisch | Chaos | Generationen von Göttern entstehen (Hesiod) | Spielball der Götter | Götterkämpfe |

| Römisch | Chaos | Göttliche Ordnung bringt Struktur (Ovid) | Teil kosmischer Ordnung | Ordnung aus Formlosigkeit |

| Nordisch | Leerer Raum (Ginnungagap) | Welt aus dem Körper Ymirs (Edda) | Von Göttern erschaffen | Weltschöpfung aus Opfer |

| Ägyptisch | Urwasser (Nun) | Sonnengott entsteht und schafft Götter | Diener der Götter | Schöpfung aus Wasser |

| Mesopotamisch | Urchaos aus Wasserwesen | Marduk besiegt Tiamat | Zum Dienst geschaffen | Kosmischer Kampf |

| Indisch | Kosmischer Urmensch | Welt aus Opfer des Purusha | Teil kosmischer Ordnung | Opfer als Ursprung |

| Chinesisch | Kosmisches Ei | Pangu trennt Himmel & Erde | Später erschaffen | Körper wird Welt |

| Maya | Leere, stille Welt | Mehrere Schöpfungsversuche (Popol Vuh) | Aus Mais geschaffen | Mensch aus Naturstoff |

Lebensgebet

Lebensgebet

Dieses Gedicht von Lou Salome hat mich schon in meiner Jugend fasziniert,

jetzt im Alter noch viel mehr.

Abtreibung

Demokratie bewährt

Demokratie schlägt Autokratie

Audio

Was spricht dafür, dass wir unsere bewährten westlichen Werte verteidigen sollten?

Der ehemalige Chefmoderator des „heute journal“ Claus Kleber berichtete in Tübingen von seinen Erfahrungen in Amerika, Europa und Asien.

Es gibt nicht die eine ideale Regierungsform, aber es gibt eindeutig bessere und schlechtere. Dass Deutschland unter der Demokratie seine längste Friedensperiode, sowie relativen Wohlstand in Freiheit erlebt hat, ist kein Zufall, sondern ihr Verdienst. Wer sehnt sich heute ernsthaft zurück in die Stasi-Gefängnisse der DDR, unter die Terrorherrschaft des Faschismus oder in jene Zeiten, in denen die Könige von Gottes Gnaden und die katholische Kirche das Volk in Armut, Abhängigkeit und Unmündigkeit hielten?

Demokratie ist anfällig für Manipulation, Medienmacht und Volksverführung – und sie kann deswegen zu falschen Mehrheitsentscheidungen führen. Doch sie garantiert, was Autokratien grundsätzlich verweigern: Meinungs- und Medienfreiheit sowie den Schutz der Menschenrechte. Diese geraten in China, Russland, Iran und zunehmend auch in den USA unter den Druck willkürlich herrschender Machthaber.

Demokratie bedeutet Rechtsstaatlichkeit, Machtbegrenzung, Machtkontrolle, sowie Mitsprache und Teilhabe der Bürger. Autokratie hingegen heißt Willkürherrschaft, Machtmissbrauch, Vetternwirtschaft und das Festklammern von Eliten und Familienclans an der Macht…bis zur Schmerzgrenze des Volkes. Siehe: Iran!

Demokratie ist die Regierungsform, die am ehesten geeignet ist, das Leid auf der ganzen Welt zu mindern und Willkürherrschaft zu verhindern. Das Ziel müsste es sein, eine gerechte und lebenswürdige Welt zu schaffen, die auf Nachhaltigkeit gründet, nicht auf immer mehr Verbrauch und Zerstörung.

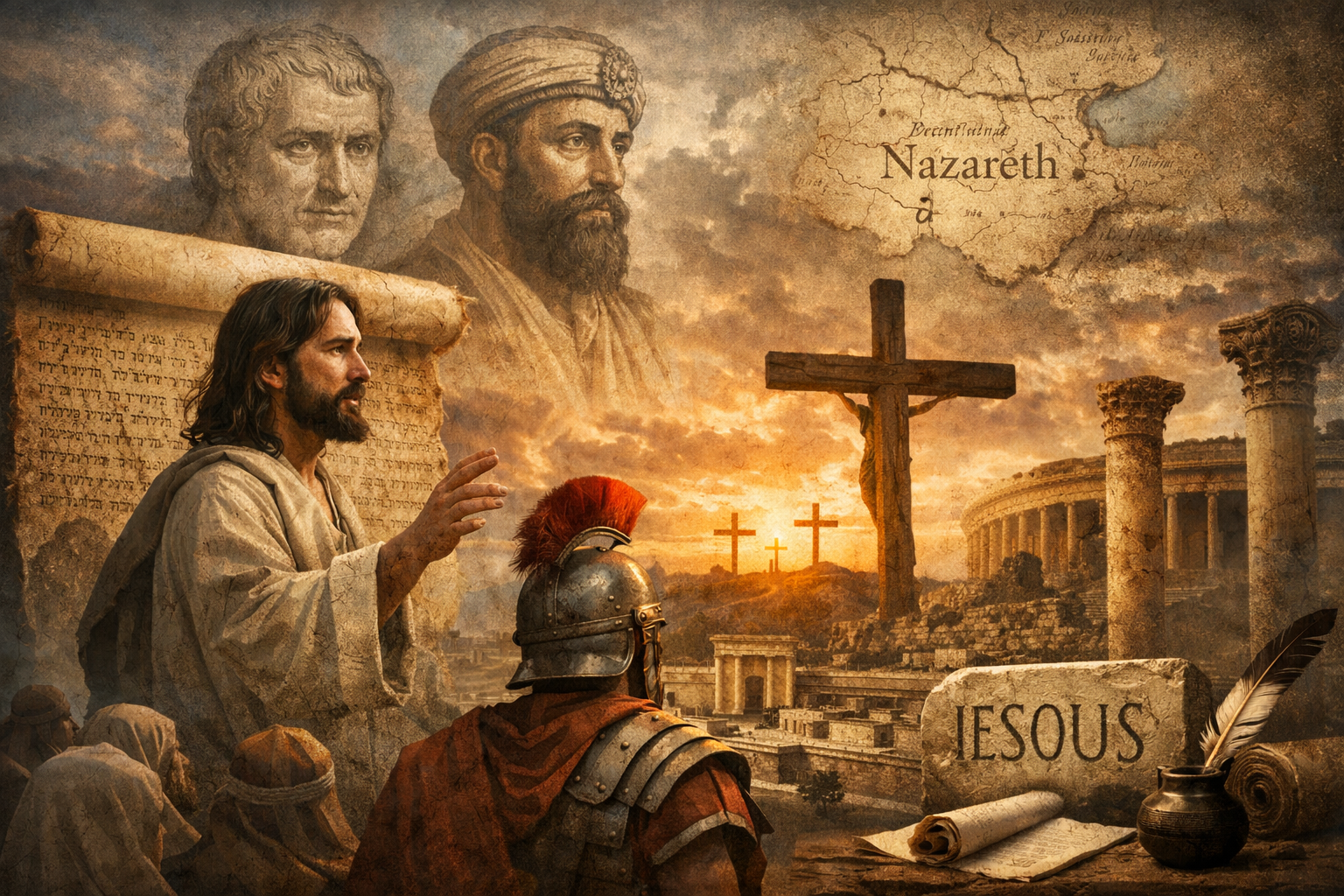

Geschichtlichkeit Jesu

War Jesus eine geschichtliche Persönlichkeit?

Audio

Für mich ist die Frage nach der historischen Existenz Jesu keine Glaubensfrage, sondern eine historische. Jesus spielt in meinem Leben keine religiöse Rolle; gerade deshalb kann ich mich ihm vergleichsweise unvoreingenommen nähern. Die glaubwürdigste Quelle für Persönlichkeitsentwicklung ist für mich die eigene Erfahrung – und aus dieser Perspektive erkenne ich erstaunliche Parallelen zwischen meiner eigenen Entwicklung und der Gestalt des galiläischen Rebellen und Wanderpredigers.

Warum ist das Christentum entstanden? Diese Frage ist nicht einzigartig. Man könnte ebenso fragen, warum der Zoroastrismus, der Buddhismus oder der Islam entstanden sind. Meine Antwort lautet: weil eine charismatische Persönlichkeit auf eine Zeit traf, die reif für eine neue Deutung der Welt war. Große historische Gestalten erkennen ihre Aufgabe in den Möglichkeiten ihrer Epoche und geben ihr einen entscheidenden Impuls. Geschichte entsteht nicht im luftleeren Raum, sondern im Zusammenspiel von Persönlichkeit und Zeitgeist.

Eine der stärksten Triebfedern historischer Prozesse ist der Wille zur Macht. Das Christentum wurde maßgeblich von sehr unterschiedlichen Persönlichkeiten geprägt: Jesus, Paulus und Konstantin. Schon diese drei stehen für drei grundverschiedene „Christentümer“. Jesus enttäuschte die messianischen Erwartungen seiner Zeit. Erwartet wurde ein militärischer Befreier, kein pazifistischer Prediger. Dass Jesus diese Rolle nicht erfüllte, spricht eher für seine Historizität: Eine erfundene Figur hätte man problemlos an die Erwartungen angepasst. Eine reale Persönlichkeit aber folgt ihrer eigenen inneren Logik.

Paulus brachte eine völlig andere Prägung ein: dogmatisch, sexualfeindlich, frauenfeindlich, staatshörig und missionarisch aggressiv. Konstantin schließlich machte aus dem religiösen Gemenge ein Herrschaftsinstrument – zur Legitimation der Macht, zur Einigung des Reiches und zur Vertröstung der Massen auf ein Jenseits. Ein solches Wirrwarr planvoll zu konstruieren ist jedoch weit schwieriger, als es organisch entstehen zu lassen. Die innere Widersprüchlichkeit des Christentums spricht eher für gewachsenes Chaos als für eine bewusste Erfindung.

Die Evangelien sind keine neutrale Geschichtsschreibung. Sie verfolgen ein klares Ziel: Jesus als den im Alten Testament angekündigten Messias darzustellen. Ihre Autoren schreiben aus dem Glauben heraus und passen die Überlieferung, wo nötig, an die Weissagungen an. Ortsangaben, Namen und Geburtsgeschichten tragen oft literarische Züge. Doch Dichtung schließt Historizität nicht aus. Dass Jesus „von Nazareth“ genannt wird, obwohl der Messias aus Bethlehem stammen sollte, deutet eher darauf hin, dass er tatsächlich aus Nazareth kam und diese Tatsache theologisch überbrückt werden musste.

Ein entscheidender Motor für den Erfolg des Christentums war die soziale Not der damaligen Zeit. Arme, Kranke, Sklaven und Entrechtete fanden Trost in der Hoffnung auf ein Jenseits, in dem die bestehenden Machtverhältnisse umgekehrt würden. Nicht die Reichen und Mächtigen, sondern die Schwachen sollten dort die Ersten sein. Dieses Versprechen war – und ist – wirkmächtig. Das Christentum ist bis heute ein Trostangebot für all jene, denen das Diesseits wenig Hoffnung lässt.

Die Römerfreundlichkeit der Evangelien bei gleichzeitiger Judenfeindschaft erklärt sich historisch. Sie entstanden nach dem Jahr 70, als klar war, dass das Judentum Jesus nicht als Messias akzeptieren würde. Abgrenzung nach innen ging mit Anpassung nach außen einher. Dass das Christentum dennoch von den Römern verfolgt wurde, spricht gegen die These einer römischen Erfindung. Der Verzicht auf den Kaiserkult und der pazifistische Grundzug der Lehre bedrohten Einheit und Wehrhaftigkeit des Reiches. Edward Gibbon sah im Christentum sogar einen Faktor für den Untergang Roms.

Tacitus schrieb: „Um das Gerücht aus der Welt zu schaffen, schob er (Nero) die Schuld auf andere und verhängte die ausgesuchtesten Strafen über die wegen ihrer Verbrechen Verhassten, die das Volk ‚Chrestianer‘ nannte. Der Urheber dieses Namens ist Christus, der unter der Regierung des Tiberius vom Prokurator Pontius Pilatus hingerichtet worden war. Für den Augenblick war [so] der verderbliche Aberglaube unterdrückt worden, trat aber später wieder hervor und verbreitete sich nicht nur in Judäa, wo das Übel aufgekommen war, sondern auch in Rom, wo alle Gräuel und Abscheulichkeiten der ganzen Welt zusammenströmen und gefeiert werden.“ Das ist das Zeugnis eines nichtchristlichen Historikers, der Jesus zwar nicht gekannt haben konnte, der aber ein wenig schmeichelhaftes Zeugnis über die Existenz der christlichen Gemeinde abgibt.

Die Werte des Christentums stehen im scharfen Gegensatz zur römischen Elitekultur: Jenseitigkeit gegen Diesseitigkeit, Demut gegen Ruhm, Sklavenmoral gegen Herrenmoral. Warum sollte die römische Oberschicht eine Religion erfinden, die ihre eigenen Grundlagen untergräbt?

Entscheidend für meine Einschätzung ist jedoch die innere Logik der dargestellten Persönlichkeit. Aus den Evangelien spricht kein übermenschlicher Weiser, sondern eine tragische, widersprüchliche Figur: ein junger Mann mit Größenanspruch, hungernd nach Anerkennung, unfähig zu gleichberechtigten Beziehungen, intolerant gegenüber Ablehnung, konflikthaft gegenüber Familie und Umwelt. Seine Brüder hielten ihn für verrückt. Die Menge schrie: „Wir haben keinen König außer dem Kaiser.“ Er verfluchte Städte, die seine Botschaft ablehnten, und Feigenbäume, die keine Früchte trugen.

Er forderte absolute Hingabe, sprach von Herrschaft, drohte und verfluchte. Er hatte Angst, betete am Ölberg und schwitzte Blut. Das sind keine Züge einer idealisierten Kunstfigur, sondern typische Merkmale eines bestimmten Entwicklungsstadiums starker Persönlichkeiten. Sie sind sehr von sich überzeugt und lösen damit ein Tauziehen aus, die anderen versuchen, sie so klein wie möglich zu machen.

Solche Figuren kennt die Geschichte: Giordano Bruno, Hölderlin, Kleist, Nietzsche, Van Gogh. Zu Lebzeiten verkannt, nach dem Tod verklärt. Starke Menschen lösen ein Tauziehen aus: Entweder sie setzen sich durch und werden zu Tyrannen – oder sie werden gebrochen. Jesus gehört zur zweiten Kategorie. Seine Kreuzigung zwischen Verbrechern, die demonstrative Demütigung, die Freilassung eines Schuldigen – all das passt in dieses Muster.

Die abrupten Umschwünge – vom jubelnden Einzug in Jerusalem zur völligen Ablehnung – sprechen ebenfalls für Historizität. Mythen sind glatt, reale Biographien nicht.

Was wissen wir also über den historischen Jesus? Es gibt keine zeitgenössischen Berichte, keine Biographie, keine eigenen Schriften. Die Evangelien sind Glaubenszeugnisse, keine neutralen Quellen. Paulus, unsere früheste schriftliche Quelle, interessiert sich kaum für das Leben Jesu, setzt seine Existenz jedoch voraus und kennt seinen Bruder Jakobus. Josephus und Tacitus erwähnen seine Hinrichtung beiläufig. Der historische Kern ist schmal, aber stabil: Jesus war ein jüdischer Wanderprediger, verkündete das Reich Gottes, sammelte Anhänger, geriet in Konflikt mit den Autoritäten und wurde gekreuzigt.

Der historische Jesus ist nicht der Christus der Kirchen. Diese Gestalt entstand erst nach seinem Tod. Wir wissen genug, um vermuten zu können, dass Jesus existierte – und zu wenig, um ihn eindeutig zu verstehen. Vielleicht liegt gerade darin seine Wirkungsmacht: Eine reale, unvollkommene, tragische Figur, die nach ihrem Tod zur Projektionsfläche für Macht, Hoffnung, Angst und Erlösung wurde.

Die Geschichte kennt viele Sieger. Jesus war keiner. Und doch hat kaum jemand die Geschichte so nachhaltig geprägt.

Jesu Größenwahn

Jesu Größenwahn

Psychologische, theologische und historische Betrachtungen

Größenwahn bei jungen Männern ist kein ungewöhnliches Phänomen. Viele machen diese Phase durch, auch ich selbst. Problematisch wird es jedoch dann, wenn solche Selbstüberhöhungen nicht relativiert, sondern religiös überhöht und sakralisiert werden. Im Fall Jesu von Nazareth scheint genau dies geschehen zu sein – mit historisch verheerenden Folgen.

Nimmt man den Größenwahn eines Einzelnen so ernst, wie er selbst es fordert, entstehen Ideologien, die Intoleranz, Ausschließlichkeit und Gewalt legitimieren. Die Geschichte des Christentums liefert dafür zahlreiche Belege: endlose Streitigkeiten über die Person Jesu, Religionskriege, Ketzerverfolgungen und ein jahrhundertelanger christlicher Antijudaismus, der letztlich im Holocaust mündete.

Was hat der „Retter“ bewirkt?

Was also hat der angebliche „Retter der Welt“ tatsächlich gebracht?

Frieden, Versöhnung, menschliche Reife?

Oder vielmehr Spaltung, Absolutheitsansprüche und ein rigides Freund-Feind-Denken?

Bereits die neutestamentlichen Texte zeigen, dass Jesus sich selbst in einer einzigartigen, übermenschlichen Rolle sah.

Jesu Selbstansprüche laut Evangelien

In den Evangelien beansprucht Jesus wiederholt göttliche oder gottgleiche Autorität:

Er lässt sich als Sohn Gottes bezeichnen (Mt 26,63), bejaht den Titel König der Juden (Mk 15,2) und erklärt sich selbst zum einzigen Heilsweg:

„Ich bin der Weg und die Wahrheit und das Leben. Niemand kommt zum Vater außer durch mich“ (Joh 14,6).

Er verkündet Heil für die Gläubigen und Verdammnis für die Ungläubigen (Mk 16,16), beansprucht Autorität über Leben und Tod (Joh 11,25) und erklärt sich für präexistent:

„Ehe Abraham ward, bin ich“ (Joh 8,58).

Nach seiner Auferstehung betont Jesus seine universale Macht:

„Mir ist gegeben alle Gewalt im Himmel und auf Erden“ (Mt 28,18).

Zugleich fordert er die gleiche Ehre wie Gott selbst und tritt als Weltenrichter auf (Joh 5,22–23).

Abhängigkeit, Ausschluss und Gewaltlogik

Jesus betont immer wieder die totale Abhängigkeit seiner Anhänger von seiner Person:

„Ohne mich könnt ihr nichts tun“ (Joh 15,5).

Wer nicht in ihm bleibt, wird „ins Feuer geworfen“ (Joh 15,6).

Damit entsteht ein klares Freund-Feind-Schema: Glaube bedeutet Rettung, Nichtglaube bedeutet Ausschluss, Vernichtung oder Verdammnis.

Besonders drastisch ist die Aussage:

„Doch jene meine Feinde, die nicht wollten, dass ich über sie herrschen sollte, bringet her und erwürget sie vor mir“ (Lk 19,27).

Hier zeigt sich ein autoritärer Herrschaftsanspruch, der mit moderner Ethik unvereinbar ist.

Vom persönlichen Anspruch zur kirchlichen Macht

Die frühe Kirche radikalisiert diese Aussagen weiter:

„In keinem andern ist das Heil“ (Apg 4,12).

Aus persönlicher Selbstüberhöhung wird institutionalisierte Heilsmonopolpolitik. Kritik wird Ketzerei, Zweifel Schuld, Nichtglaube ein moralisches Verbrechen.

Fazit

Jesus erscheint in den Evangelien nicht als bescheidener Weisheitslehrer, sondern als Figur mit extremen Selbstüberhöhungen: Sohn Gottes, Weltenrichter, einziger Heilsweg, Herr über Leben und Tod.

Nimmt man diese Aussagen ernst – und genau dazu zwingt das Christentum –, dann trägt nicht nur die Kirche Verantwortung für Intoleranz und Gewalt. Bereits die Ursprungstexte selbst legen diese Entwicklung nahe.

Der religiös legitimierte Größenwahn eines Einzelnen wurde zur Grundlage einer Weltreligion – mit Folgen, die Millionen Menschen das Leben gekostet haben.

Ergänzende Zitate

Jesus hält sich für den Mat:26:63 Sohn Gottes und den Mark:15:2 König der Juden Er behauptet: Joh. 14:6 „Ich bin der Weg und die Wahrheit und das Leben. Niemand kommt zum Vater außer durch mich.“ Mk. 16:16 „Wer glaubt und sich taufen lässt, wird gerettet; wer aber nicht glaubt, wird verdammt werden“. Mat. 23:8 Aber ihr sollt euch nicht Rabbi nennen lassen; denn einer ist euer Meister, Christus; ihr aber seid alle Brüder. Joh. 8:51. „Wahrlich, wahrlich ich sage euch: So jemand mein Wort halten wird, der wird den Tod nicht sehen ewiglich“; und Joh. 8:58 „Wahrlich, wahrlich ich sage euch: Ehe denn Abraham ward, bin ich.“ Math 26:61 „Er hat gesagt: Ich kann den Tempel Gottes abbrechen und in drei Tagen aufbauen.“ Joh. 15:5 Ich bin der Weinstock, ihr seid die Reben. Wer in mir bleibt und ich in ihm, der bringt viele Frucht, denn ohne mich könnt ihr nichts tun. Jesus betont die Abhängigkeit der Jünger von ihm für ihre geistliche Fruchtbarkeit. Joh 11:25 Ich bin die Auferstehung und das Leben. Wer an mich glaubt, der wird leben, ob er gleich stürbe; Luk. 19:27 „Doch jene meine Feinde, die nicht wollten, dass ich über sie herrschen sollte, bringet her und erwürget sie vor mir.“ Er vernichtet seine Gegner und Kritiker Joh. 15:6 Wenn jemand nicht in mir bleibt, der wird weggeworfen wie eine Rebe und verdorret, und man sammelt sie und wirft sie ins Feuer, und sie müssen brennen. Wer nicht sein Anhänger sein will wird ins Feuer geworfen. Apostelgeschichte: 4:12 12 Und ist in keinem andern-Heil, ist auch kein andrer Name unter dem Himmel den Menschen gegeben, darin wir sollen selig werden. (als Jesus) Absolutheitsanspruch der Kirche. Matthäus 16:15-17 – „Da spricht er zu ihnen: Ihr aber, für wen haltet ihr mich? Simon Petrus antwortete und sprach: Du bist der Christus, der Sohn des lebendigen Gottes! – Jesus bestätigt hier die Erkenntnis von Petrus und bekräftigt seine Identität als der Sohn Gottes. Johannes 5:22-23 – „Denn der Vater richtet niemand, sondern hat alles Gericht dem Sohn übergeben, damit alle den Sohn ehren, wie sie den Vater ehren. Wer den Sohn nicht ehrt, ehrt den Vater nicht, der ihn gesandt hat.“ – Jesus betont seine Rolle als Richter und fordert die gleiche Ehre, die dem Vater zusteht. Johannes 10:17-18- „Darum liebt mich mein Vater, weil ich mein Leben lasse, auf dass ich’s wiedernehme. Niemand nimmt es von mir, sondern ich lasse es von mir selbst. Ich habe Macht, es zu lassen, und habe Macht, es wiederzunehmen. Dies Gebot habe ich empfangen von meinem Vater.“ Jesus spricht über seine Autorität über Leben und Tod. Matthäus 28:18- „Und Jesus trat zu ihnen und sprach: Mir ist gegeben alle Gewalt im Himmel und auf Erden.“- Nach seiner Auferstehung betont Jesus seine umfassende Macht und Autorität. Lukas 4:18-21“Der Geist des Herrn ist auf mir, weil er mich gesalbt hat und gesandt zu verkündigen das Evangelium den Armen; Und er fing an, zu ihnen zu reden: Heute ist diese Schrift erfüllt vor euren Ohren.“- Jesus erklärt, dass die prophetische Schriftstelle aus Jesaja in ihm erfüllt ist. Johannes 14:9 – Jesus erklärt, dass das Sehen ihn gleichbedeutend mit dem Sehen des Vaters ist. z. B. Matthäus 28,18) > „Mir ist gegeben alle Macht im Himmel und auf Erden.“

→ Spätestens hier wird deutlich: Jesus sieht sich als universaler Herrscher.

Jesus beanspruchte Herrschaft.

Er verstand sich als König eines anderen Reiches, als göttlicher Gesandter, aber zugleich als derjenige, dem am Ende alle Macht zusteht.

Pahlavi

Wie Königsdynastien enstehen

Wie Königsdynastien entstanden, am Beispiel der Pahlavis, die sich dann den Titel „König der Könige“ gaben und 1971 das 2500- jährige Thronjubiläum feierten, das 300 Millionen Euro kostete. Der Großvater des heute in den USA lebenden Sohnes des geflohenen Schahs – also Reza Schah Pahlavi (Reza Shah Kabir) – war nicht von adliger Abstammung. Seine Herkunft war bescheiden und militärisch geprägt: · Einfache Herkunft: Er wurde 1878 in eine Familie mittleren bis einfachen Standes in der Provinz Masandaran geboren. Sein Vater und Großvater waren Militäroffiziere, aber keine Adeligen. · Militärkarriere: Reza Schah trat als einfacher Soldat in die persische Kosakenbrigade ein und stieg durch außergewöhnliche Fähigkeit und Charisma bis zum Kommandeur auf. · Selbstgemachter Mann und Dynastiegründer: Durch einen Putsch ergriff er 1921 die Macht und ließ sich 1925 zum Schah krönen. Er begründete die Pahlavi-Dynastie, d.h., er schuf den neuen „Adel“ bzw. die Herrscherfamilie erst selbst. Zusammenfassung: Reza Schah war ein „self-made man“ und kein gebürtiger Adeliger. Er stammte aus einfachen Verhältnissen und errang den Thron durch militärischen und politischen Aufstieg. Seine Nachkommen (sein Sohn Mohammad Reza Schah und sein Enkel Reza Pahlavi) sind dann natürlich durch ihn als Dynastiegründer zu königlichem Blut geworden. Fast jede Dynastie begann mit einem Emporkömmling, der dann für seine Nachkommen königliche Rechte gemäß königlicher Geburt einforderte. …und die Leute glaubten den Unsinn.

Siehe: rolandfakler.de/koenigsdynastien